Another reflective exercise as part of my Citizenship studio, was one of writing a citizenship story in relation to your own Self. I chose to write mine on the topic of nation as body, of belonging or not belonging to a nation, a national community, a shared sense of self, self as in “I” as part of a “we”.

Essential to the Conflictual Harmony lens is an awareness of the norms, identities and power structures tied to them that operate in any human context, as a basis for strategic intervention that goes to the root of a problem. The construction of ideas of whiteness and blackness is one that has come to define my thinking, my life and my understanding of the world in crucial ways, teaching me about dynamics of power, identity and Othering mechanisms applicable in a variety of unrelated configurations.

It’s also a particular identity construction that I believe is worth understanding in relation to the institutional culture that upholds much of our national identity in a Sweden with a long tradition of technical rationality and other values associated with the construction of whiteness. The purpose of this exploration to provide a basis for a deeper transformation, a whole systems change that takes into account not only the specific bodies that are marginalized in a particular context, but seeks to transform also the norm systems, the alienating roles (across the board) and the organizational cultures tied to them.

So here comes my story:

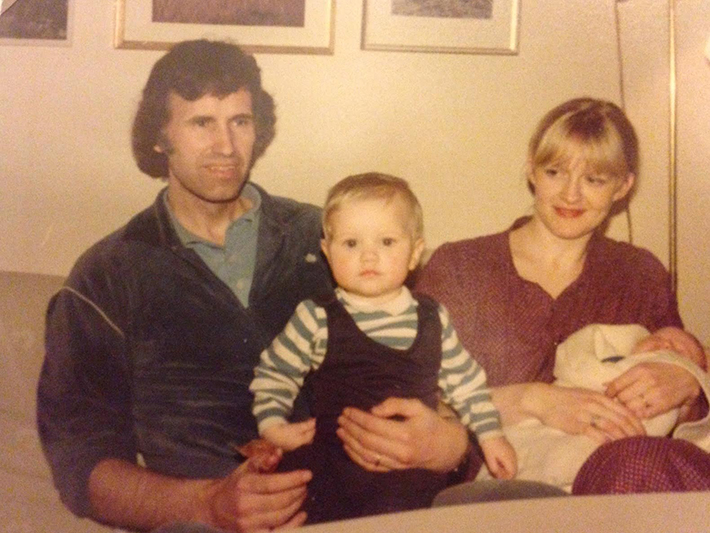

I was born into a body labelled as Swedish, female, and, to be found out way later, white. This body grew tall, slim, with blonde hair and blue eyes, the embodiment of racial superiority claims that Sweden hid into dark corners of its past, silenced into oblivion.

Growing up, I did not know I was white, or that the social group my family gave me access to was particularly different from the people I grew up with, coming from places as dispersed as Yugoslavia, Eritrea, Lebanon, India, Chile and Iran. I knew little about the connection between whiteness and Swedishness, embodied citizenship if you may say and the loyalties, expectations, boundaries and norms to live up to as a member of a larger family of white Swedish people. I knew little about the privilege I held, the special status I had in relation to other bodies of a different color than mine, or a different citizenship status.

The belief in your own whiteness I find, does not always come in a conscious form and it may be exercised also by people with strong loyalties to the constructions of whiteness. It comes through association, a seemingly innocent idea of your right to your special place in the world. Your right to label things, feel sorry for people, help them and protect them or protect yourself from them, a belief in the otherness of them, their unique nature and spirit and culture that is separate from you. It comes through the indignation when something doesn’t go your way, the idea that this “should not be happening to me”. A missed flight, delayed baggage, time-consuming routines exercised by a government official. Meanwhile bodies not granted the same status sink to the bottom of the oceans in their attempts at reaching the promised land of Europe, dying nameless, with no story and no humanity attached to them.

In the words of Richard Wright, African-American author of “Black Boy”, the idea of whiteness, as any constructed identity upholding a certain position of power, also comes along with an alienation from self, an inability to see clearly yourself from the outside, from a different point of view. It comes with an obsession with the world around, what needs to be fixed and controlled and groomed and perfected, put in order. Sometimes, it comes with an innocent “awareness of your privilege”, smiling awkwardly at those lower than you in status, asking for their input out of pity and maintained otherness, granting them the status of “all-knowing experts” instead of contradictory, messed up, beautiful, smart and stupid people like you.

What I did know growing up, past age 12 or so when the process of social conditioning and affirmation of loyalties-self-identities-adult norms to live by, really kicked into motion, was that it was hard to breathe in this body I had been born into. It did not seem to fit the chaos, the life force, the intense search for meaning and purpose and need to express myself that I carried since I was a young child. I resolved my situation by sheer force of mental control, locking myself into an alienated state of intellectual bliss and accomplishment, idolizing the great male European philosophers. “It’s really true” I would think, that “this existence of ours is defined by its lack of purpose and alienation of self, that this is built into our human nature”. Little did I know, it was built into my own unconscious belief in myself as a white person, defined by the conquering of mind over body, spirit over matter.

Where did I learn about my own whiteness then? Where else than in the American South, the land of historic racial segregation and madness, but also one of painstaking clarity in terms of constructions of race as it relates to self, community and nation formation. In the American South, I learnt to see my own whiteness, its loyalties and inherent contradictions. I learnt about this by meeting black, an equally alienated construction, though painfully aware of its counterpart of white (in the words of Kara Walker), “my Complement, my Enemy, my Oppressor, my Love”.

In the South, I learnt about the deeply interconnected nature of constructions of white and black, how one cannot exist without the other. Where black is obscure and mysterious, white is enlightened and clear, where black is entrenched in the body, white carries the spirit of the mind. Humanity divided into two constructs fed by belief and manifested in social structures, with one granted second class citizenship, and the other left with the burden to uphold a status of the all-knowing, ever-perfect, morally superior and refined superhuman, fearful of filth, chaos, and being exposed of immorality or sin of any kind.

How did I experience this drastic shift in consciousness? I experienced it as social schooling, a lens to see the world through, exposing layers of dominance and hidden assumptions I was previously unaware of. I experienced it as an emotional and bodily sensation, opening up to the other as myself, through stories of oppression feeling my own pain of suppressed emotions, aliveness and sense of self. I experienced it as a spiritual awakening, in glimpses of letting go of social conditioning and experiencing myself in my full vibrancy, beyond ideas of what I am or what I should be.

Skipping over a long period of confusion, frustration, inspiration and very constructive and creative social movement work upon my return to Sweden, I will jump right into my analogy of body-as-nation. Self connected to nation, nation and its public institutions as the embodiment of the ideals laid upon its people, people and government in close interrelation, feeding one another in a reciprocal relationship. The Swedish nation and its institutions as embodiment of white ideals, marginalizing those that are othered by it, but also creating a body that doesn’t breathe, that doesn’t allow for imperfection, for humanity, for flexibility, movement, critical self-examination , and an awareness of its own reliance on its people and trust in its people for its future growth and wellbeing. A body that looks and examines and determines but is not able to take in its Other looking back. A body that doesn’t engage in true exchange, fearful of what it might meet in the eyes of the Other?

My final words will start off with a quote from Franz Fanon, that in the end “there is no black soul, and there is no white burden.” It is all made up, constructed, as is the nation-as-body that doesn’t breathe. Do I believe in this body, in its ability to start moving, start breathing, face its own pains and imperfections, breathe with the changes towards a citizenship that grows with the people that enter its land? I believe I do. As a body living on this earth, cosmopolitan as I may be, I am also tied to the national community where I first felt the wind in my face, the soil against my bare feet, tasted the blueberries and smelled the salty-sweet waters. Not believing in the institutions and culture that raised me, would be not believing in myself, in the potentialities of this self, its abilities to grow and learn.

Self as nation, nation as self, living inside a larger sense of global connectedness and solidarity. I believe it’s possible.

Sign up to receive notifications of new posts via e-mail.