What is the future of scholarly knowledge and higher education? What are the changing contextual landscapes surroundings our university systems, the external pressures and internal tension points? How could these tension points be used to strengthen the university system as a whole in the face of a complex set of rapidly changing economical, political as well as social factors?

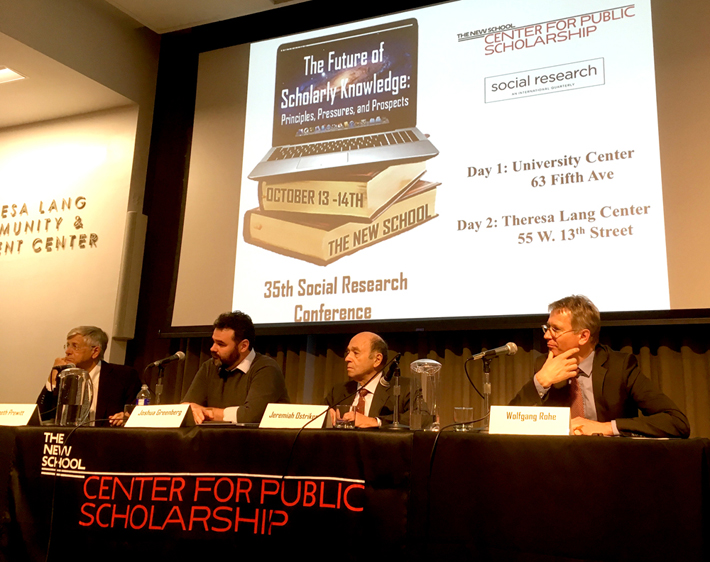

At the New School conference “The future of scholarly knowledge” – held on October 13-14 – I was introduced to an overview of “principles, pressures and prospects” in regards to the university system, as expressed by representatives from the humanities, social and natural sciences. In this blog post, I will conduct an initial thought experiment on what role design and systems thinking could play in facilitating a constructive path forward for an educational system struggling to define its direction in a period of transformation.

The changing landscape discussed during the conference included external “competitors” like google, think tanks and individuals making knowledge-claims previously reserved for members of the university system – actors thinking and responding faster and in more communicative ways than traditional universities. Political and economic pressures included demands for practical payoffs, standardized metrics and performance auditing, as well as the heated topic of “identity politics”, and the “demand” for trigger warnings, safe spaces for minority groups and recruitment based on affirmative action.

Several of the speakers expressed the perceived threats in response to these pressures – including the loss of “free intellectual play”, “the value of seeking knowledge purely for the human spirit”, autonomy of research, the unrestricted dissemination of information, and the “freedom” in appointing academic staff “without regard to sex, ethnic or national characteristics, or political and religious beliefs”. The value of free speech was painted by several of the speakers as in opposition to demands of social justice and accommodation of the expressed needs of minority groups, creating a “politically correct” environment defined by “guilt by association”, fear of defending arguments that are not politically correct, and a viewpoint diversity replaced by “tribal identity” where “everyone only cares about their own perspective”.

“The other side” of this account – the minority groups, the younger generation, the women – were strikingly absent from the discussion and in the room itself. One of the speakers ironically referred to the outcry of some of the other members of the panel as “let´s make scholarship great again!”, another (the only woman on the panel) pointing out that “if this is the public sphere of enlightenment we´re in trouble”.

So where does this conversation lead us? As a social activist, I could easily disassociate from the viewpoints and perspectives expressed, brush the conference off as a bunch of old, white men mourning lost hierarchies and power, and go on formulating claims in favor or minority rights in university settings. This is obviously a position that needs to be filled, and that is increasingly filled through elaborate discourse on topics of gender, queer and racial concerns and advocacy on behalf of these groups within an educational system historically dominated by white males. As a Transdisciplinary Designer however, I recognize that this is not the role I´m there to fill, and instead, I search for the missing communication links, the cognitive contradictions or openings, and the transformative and creative potential of any situation encompassing conflict and differing agendas, perspectives and experiences.

So what are the principles upon which I lean in my continued thought experiment on what role Transdisciplinary Design could play in a scenario such as the one presented to me during this conference?

First of all, my scope of concern is the entire system. In “Thinking in systems”, Donella Meadows defines a system as “a set of things interconnected in such a way that they produce their own pattern of behavior over time” (2). A single university is a subsystem of the larger university system, involving elements like faculty and students, but also intangibles like the value of “free speech”, “free research” etc. Thinking in systems, I cannot disregard the element of the dissatisfaction expressed during the conference any less than I can disregard the perspectives of the students, the minorities or the women, since they are all part of the overall system I´m trying to optimize. Instead of focusing on who is “right” and who is “wrong” my focus is on facilitating the birth process of what constructive action or outcome that this conflict could have emerge. Speaking in systems, this could also be described as focusing on flows rather than stocks, with the stocks being the actual elements/things of the system, and the flows the interconnections between them, such as the platforms for communication.

Second, from a systems perspective I would identify the strengthening of the resilience of this system as a major leverage point for creating adaptability in face of a changing political, social and economic environment. “A system that can evolve can survive almost any change, by changing itself” (159). The influx of new demographics, new perspectives and experiences into the university system all create opportunities for strengthening this adaptability of the overall system. However, this potential will only be fulfilled under the condition that the “flows” in between the different elements of the system are kept fluid, communicative and creative rather than resulting in a “war” creating more rigidity as both sides build their arms and their resistance against each other.

So, if this conflict surrounding “identity politics” could be seen as a major leverage point in ensuring the adaptability of the overall university system, what are ways to move forward?

First, I would look for ways to understand the conflict at hand through the concept of “bounded rationality”, meaning “that people make quite reasonable decisions based on the information that they have” (107), from their particular vantage point in the system. We further learn that “policy resistance comes from the bounded rationalities of the actors in a system, each with his or her (or its) goals. Each actor monitors the state of the system with regard to some important variable and compares that state with his, her or its goals” (113). This is clearly illustrated by the focus on free speech and autonomy expressed by several of the professors – goals that from their perspective seem objective and unquestionable – but that from a non-male non-white perspective would be revealed as clearly biased in favor of particular bodies and experiences. Meadows says that “the most effective way of dealing with policy resistance is to find a way of aligning various goals of the subsystems, usually by providing an overarching goal that allows all actors to break out of their bounded rationality” (115).

Based on this line of thought, I would see it as my role to facilitate meeting spaces for mutual reflection, through a careful scrutinization of what “the other” values and strives for, beyond assumptions and name callings. “That calming down may provide the opportunity to look more closely on the feedbacks within the system, to understand the bounded rationality behind them, and find a way to meet the goals of the participants in the system while moving the state of the system in a better direction” (114).

One speaker at the conference, Akeel Bilgrami, made an effort to frame the issue in this direction, by looking at the potential gaps in understanding from a generational viewpoint. Needless to say the generational lens is not exhaustive and would need to be complemented with additional lenses identified as being of importance from both sides, but for the sake of this blog post, I will use Akeel´s example to illustrate a way of thinking I believe is of utmost importance for the constructive approach to the issue at hand. According to Akeel´s inquiry, “free speech” means something very different to those who experienced the Cold War´s climate of inhibition and threat, and the younger Internet generation who have seen “free speech” be used as an excuse for abuse and offense. Akeel suggested that the younger generation are seeking a model of academic inquiry in humanities similar to that of transitional justice within law, where there are certain constraints on the “freedom” of the inquiry in the name of fairness, under the condition that one has to “live with the future of the ones you are judging”. This form of inquiry is therefore not a detached one (as in academic inquiry today), but an engaged one, where your “object of investigation” is given space to speak. Another speaker at the conference emphasized the need to learn to see not through each other, but into each other, a third mentioned a possible aspiration for a modern university environment to “imagine the place of the other” (I´m assuming, whoever this “other” is).

Could design help facilitate this closeness and engagement with that which you are judging (on both sides) in the creation of “safe spaces” where both sides can meet on an equal ground, talking to, rather than about each other? Could we map perspectives, goals, fears, frustrations, values, hopes and what they mean to different stake holders in concrete situations and touch points? Donella teaches us that “We change paradigms by building a model of the system, which takes us outside the system and forces us to see it whole” (164). Could we then use design tools to visualize and understand the creation of alternative futures, alternative university principles and their translation into concrete materialized outcomes? Could this open up for a collective re-definition of the traditional values of the educational system into a more expansive definition, including those that were previously excluded? Could it assist in the creation of alternative measures of accountability defined from within as opposed to demanded from the outside? Could exercises of this kind help alleviate the need for rules and regulations to “protect” those marginalized by the traditional system, by working towards a space of constructive co-creation rather than that of an “oppressor” and an “oppressed”?

Any pursuit of conflict transformation of this kind is most certainly a challenging one, but also an arena with much transformative and creative potential in terms of breaking out of our old mental models and systems. The role of the designer thus to look carefully for possibilities, openings and constructive ways forward, allowing space for conflict held in the embrace of a firm belief in an underlying dynamic unity in the midst of conflicting world views, fear, resistance and legitimate claims for a more inclusive educational system. It´s a mighty task indeed in times such as ours, but also, as the recent election has shown, more important than ever.

This post was originally written as part of the course “Transdisciplinary Seminar” taught by Jamer Hunt at Parsons/The New School.

Sign up to receive notifications of new posts via e-mail.