What: Transdisciplinary

/Service Design and scriptwriting/filmmaking for End of Life studio as part of the Transdisciplinary Design program at Parsons/The New School in New York City.

My role: Designer along with Nandita Batheja and Charles Margaritis. My focus being primarily on script writing, research and strategy.

In my first studio class at Parsons, taught by design strategists John Bruce and Patty Beirne, we delved into systemic issues of the American health care system and specifically end of life care. The design intervention my team proposed consisted of a new role within the larger service eco system: The Patient and Family Advocate.

To understand overall systems issues we referred to secondary ethnographic research, focusing on the persistent rescue culture within the American health care system (read more about this culture and its effects below). Each team then zoomed in on a specific moment of crisis within this system. We used additional research, script writing and film making to understand the experiences of patient, family and staff involved in the particular scenario we had chosen. Based on this understanding we moved on to ideation, prototyping and concept development to land in our intervention.

From the syllabus: “Through this studio course, students will learn to engage empathic design within complex systems not from the role of “problem solver”, but as “experience strategists.” By developing and then engaging a set of design principles and tactics drawn from a reframing of the opportunity space, students will set a stage for re-envisioning the experience of disease and dying as we know it today”.

Read our account of our “moment of crisis below”:

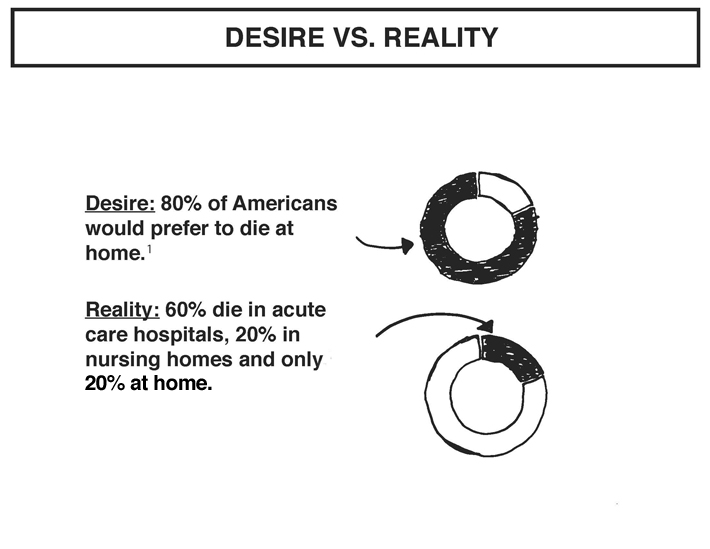

At what moment does someone decide “enough is enough” when it comes to the aggressive medical treatment of a terminal disease? When does the doctor determine that the patient has “six months or less” to live, making them eligible for hospice? When/how does the doctor tell the patient that? Where do the facts get muddled by each stakeholder’s individual desires (to prolong life, to remain optimistic, to help…)? How is this choice influenced by the apparent hierarchies of services, where social recognition and value is given to rescue effort, and hospice or palliative could be perceived by patients and their families as abandonment? What structures are in place to support the patient and their families in the evaluation of the situation, and the existential and emotional needs of those facing a situation where “battling the disease” seems more and more like a lost war?

After three chemotherapy treatments, 34 year old Sara sits in an office with her doctor, her husband and her parents. A friend looks after their newly born child at home. The first two treatments of chemotherapy already failed. Sara’s CT scan shows that the last one has been unsuccessful as well. The tumor depots have grown substantially. The doctor and the family sit together to discuss what to do. There is another drug they could try, though only a small percentage of people had experienced extended life upon taking it, and that extension was only an average of two months.

This scene explores the complications, multiple hierarchies, miscommunication, emotions, desires and conflicts that arise in the conversation about how to move forward. Family input, doctor discomfort and influence, the newly born child, Sara’s personal connection/investment to each stakeholder–and to her own desire to live–all emerge as interwoven, weighted factors as they collectively work towards a decision and an approach to a situation that provides little hope for much time left.

See our final presentation as well as our films below. For a more complete account of our research and process, you can download our Documentation Book. To read the full script of the Moment of Crisis (abbreviated version presented in the video below), click here.

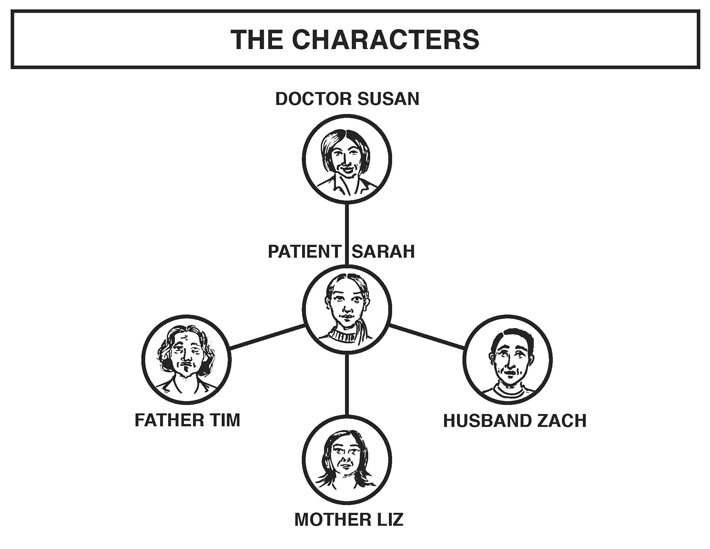

We narrowed in on a case study that involves a young woman – Sara –her husband, father, mother and doctor. These characters are based off a composite of true stories and testimonials.

Sara was 8 months pregnant with her first child when she learned she was going to die from lung cancer. Everybody was trying to save this woman. She underwent induced labor so doctors could start her on treatment immediately. The baby survived – healthy and safe – but Sara’s cancer didn’t respond to the drugs. After two more treatments, she and her family meet with the doctor only to learn that the third treatment was not successful.

The absence of authentic communication leads to a decision about end of life treatment that just happens – without any discussion around what that decision really means or what´s at stake. Everyone in the room sticks with the “fight” response without considering other paths, like hospice – in fact, that isn’t even raised as an option.

Performers: Johanna Tysk as Sarah, Daniel Grossman as Zach, Renée-Michele Brunet as Susan, John Bruce as Tim, and Patty Beirne as Liz.

Save

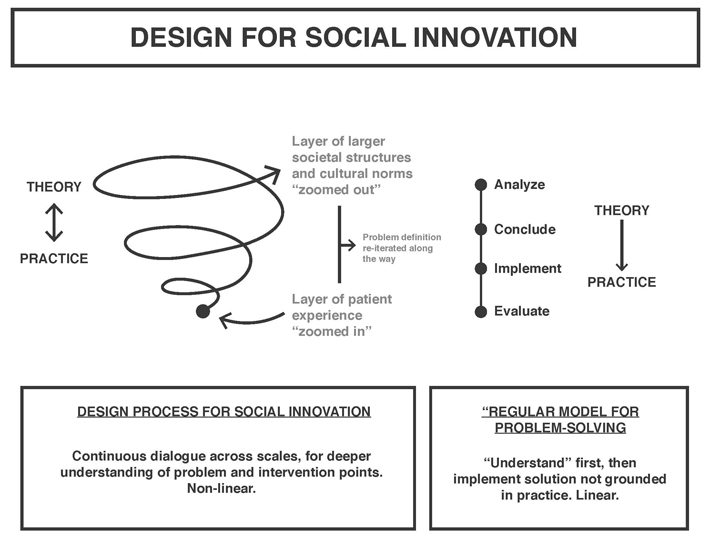

The graphic above briefly explains the process of design for social innovation. It can be seen in contrast to the “standard” linear process of problem-solving regularly exercised by a variety of disciplines.

As in our study for this class, design for social innovation involves a constant going back and forth between theory and practice, larger structures and individual experiences.

Save

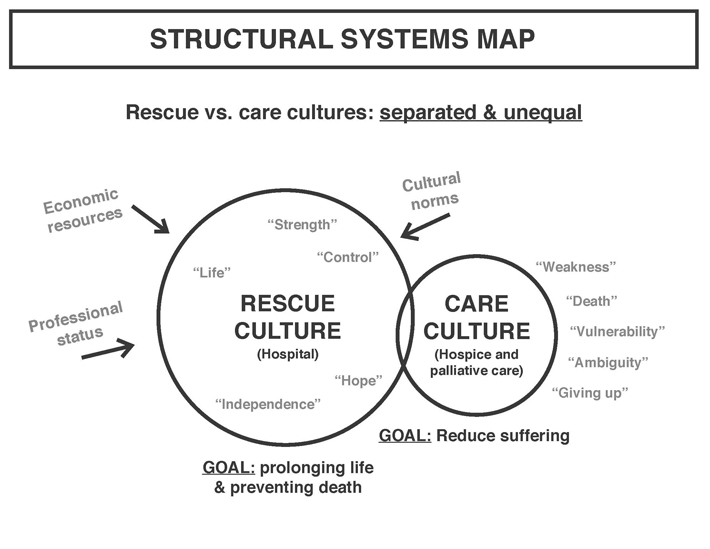

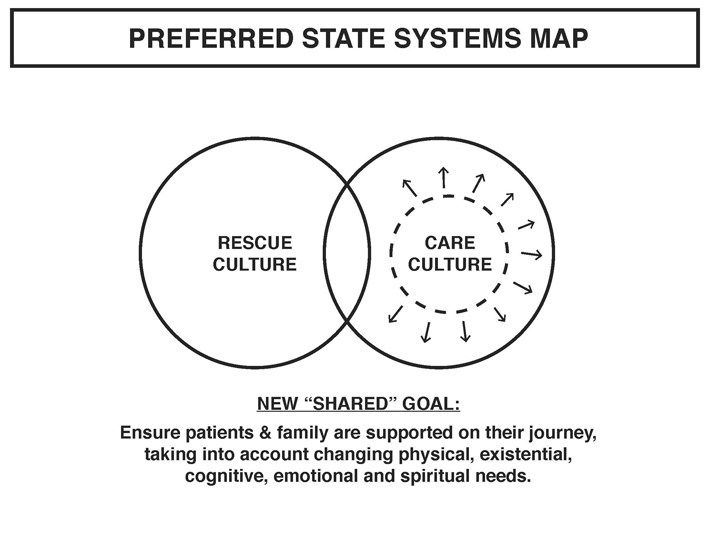

Through our research, we discovered two cultures within the healthcare system: the culture of rescue and the culture of care, most clearly tied to the hospital and hospice or palliative care units. They each have their distinct goals and purpose. Rescue culture aims at prolonging of life: employing state-of-the-art technology and medical expertise. Care culture aims at reducing suffering, through “soft care”, accounting for pain reduction on physical and emotional levels.

Economic resources, professional status and cultural norms create an imbalance between these two cultures, represented by the size of the circles. The words listed in each circle represent some of the normative associations with each culture.

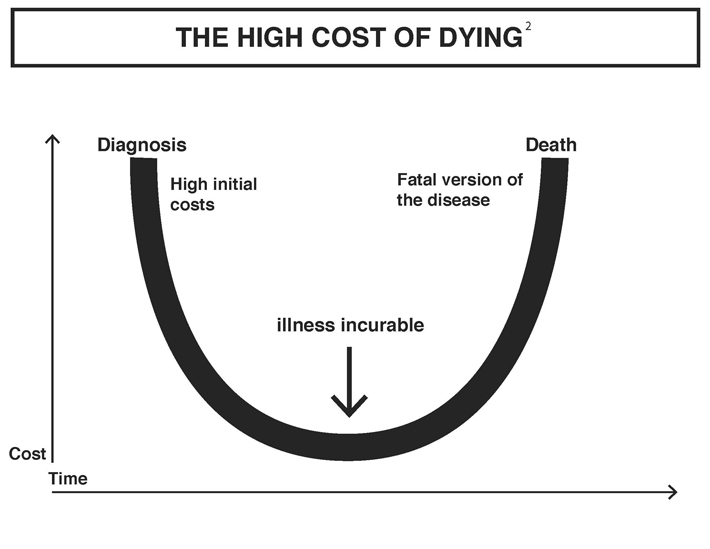

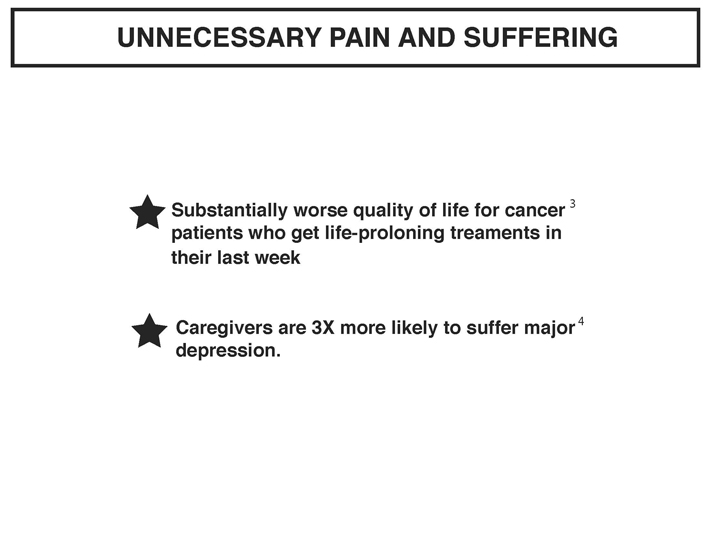

These structures and associations result in crucial decisions and outcomes. The fight-till-the-end mentality is also extremely expensive. It creates prolonged hospitalization and soaring medical bills. On top of that, there are the emotional costs.

Save

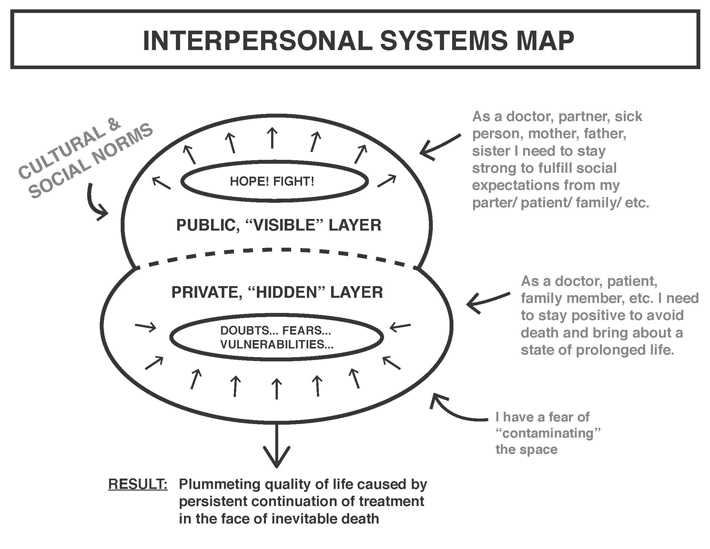

Zooming back in to our scene involving Sarah, we can look at this scenario through the lenses of a public layer in the office and a private layer revealed through their testimonials.

In the public layer we see the characters feed into one another’s hope and fight mentality. In the private layers are doubts, fears and vulnerabilities, kept hidden due to perceived expectations from the others.

The separation of the two layers leads to the traumatic and tragic end of Sara’s life.

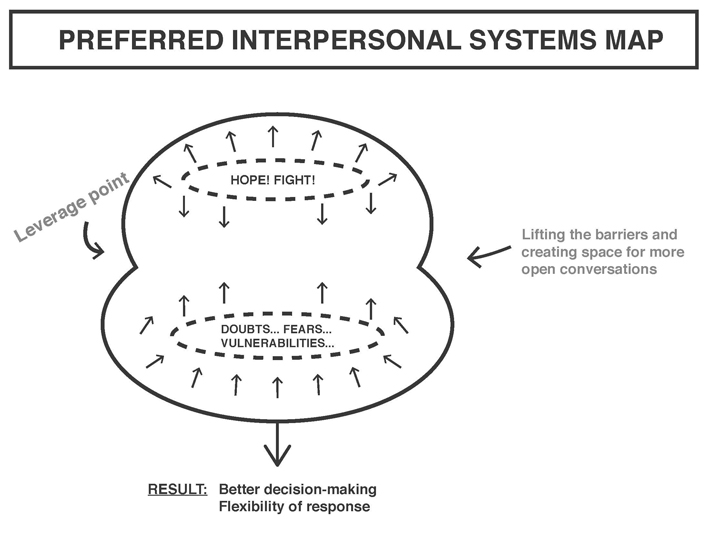

So we asked, how can we bring these layers into conversation in the public sphere?

When you do that, there will be tension, insecurities, possible conflict. How do we then navigate this complexity in a productive way, use it for more open and honest communication and better decision making?

Save

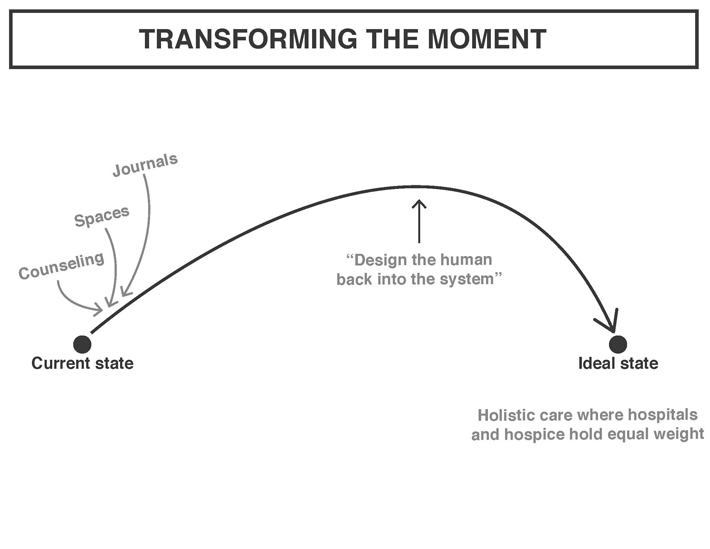

We considered a number of tools: journals, physical spaces, digital platforms, arts practices, counseling tools…

But none of them seemed sufficient. Simply exposing the underlying doubt, confusion, tensions doesn’t help; that results in panic. We realized we’d need a way to navigate the tension. We need a person. Someone with the competence of a counselor, but the ability to also work directly with the doctors, addressing their doubts and their internal struggles connected to their profession.

In order to leverage that moment of crisis we need someone who can intervene with the hierarchies and silos of the rescue vs care cultures within the larger eco system of care.

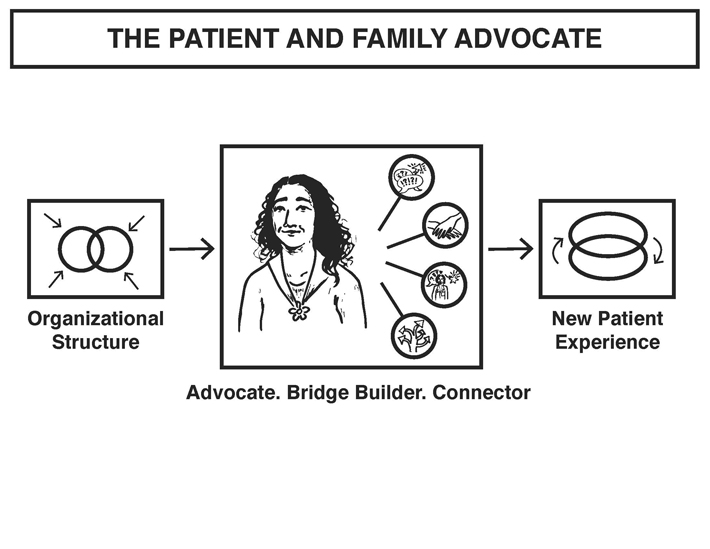

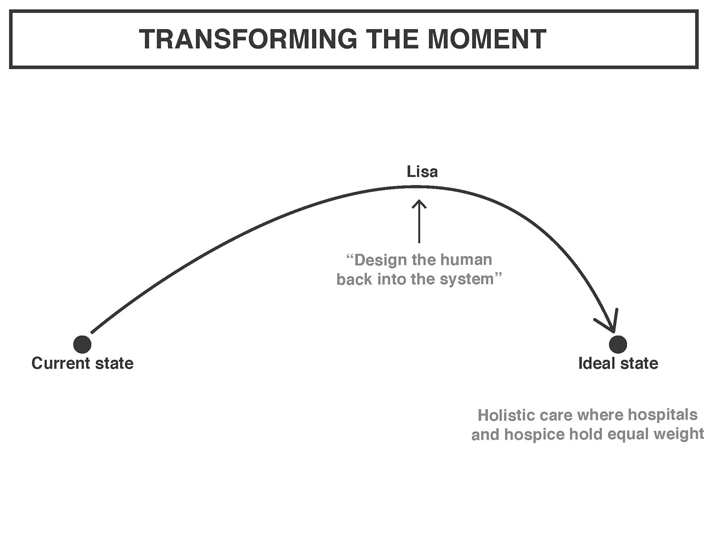

And that’s how we got to Lisa, our Patient and Family Advocate.

Performance by: Nandita Batheja.

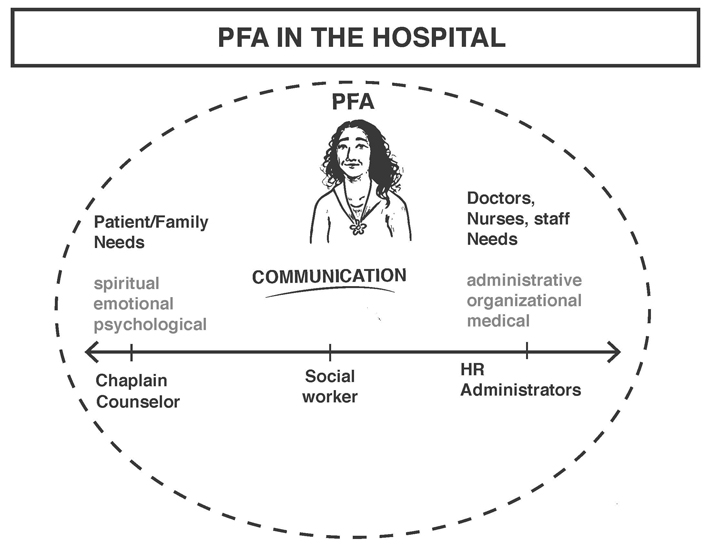

Lisa advocates on behalf of patient and family needs through in-person meetings, phone calls and facilitation of difficult conversations.

Lisa advocates on behalf of patient and family needs through in-person meetings, phone calls and facilitation of difficult conversations.

She connects them with external support services throughout their journey.

She builds bridges across health care departments through facilitation of training, workshops and knowledge exchange.

This role cannot stand alone however. We also identified a need for a new organizational structure to support this role. Together they result in an altered patient experience.

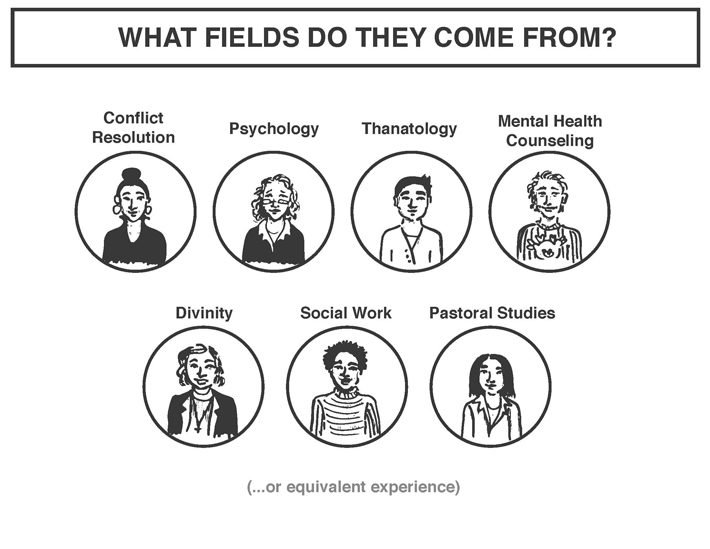

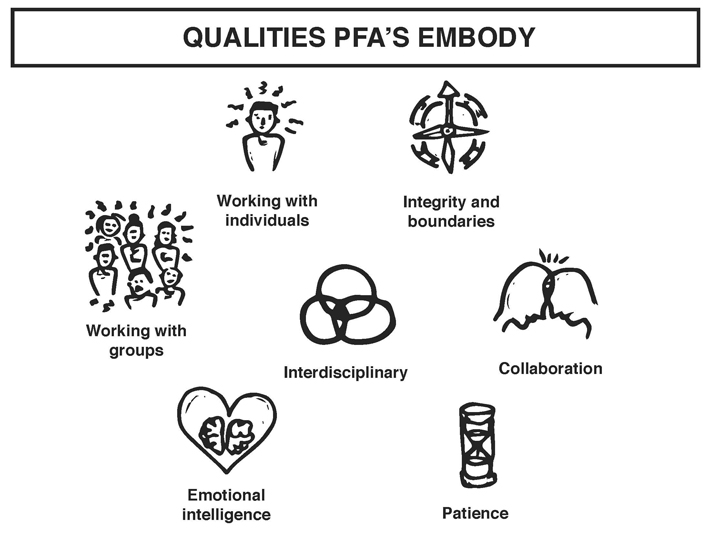

What all PFA´s share is a deeply interdisciplinary background and the ability to communicate within both cultures: rescue and care. They play multiple cultural roles, but their task is always the same: to facilitate better communication and provide space for people to be themselves.

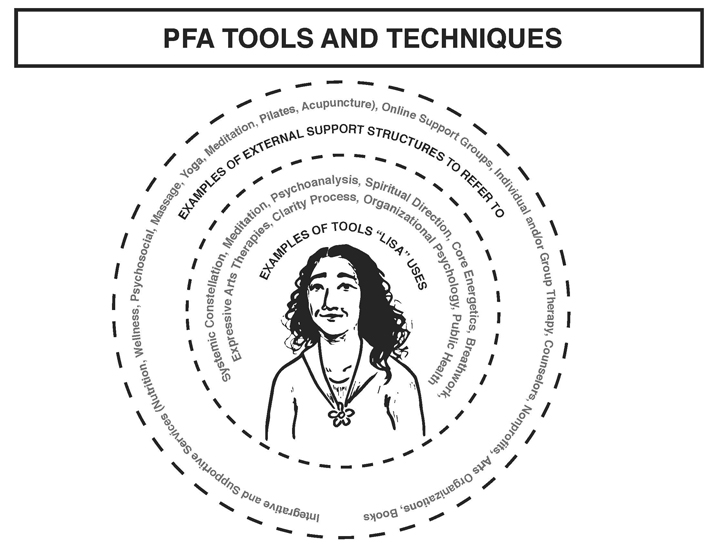

The needs of all stakeholders filter through Lisa and she discerns what tools and services apply.

The needs of all stakeholders filter through Lisa and she discerns what tools and services apply.

For patients she may use: Systemic Constellation, Meditation, Expressive Arts Therapies. Or, she may direct them to external supports: oncology massage, Individual counselor, Books.

For doctors and staff, she’d call upon tools and knowledge from organizational psychology and public health.

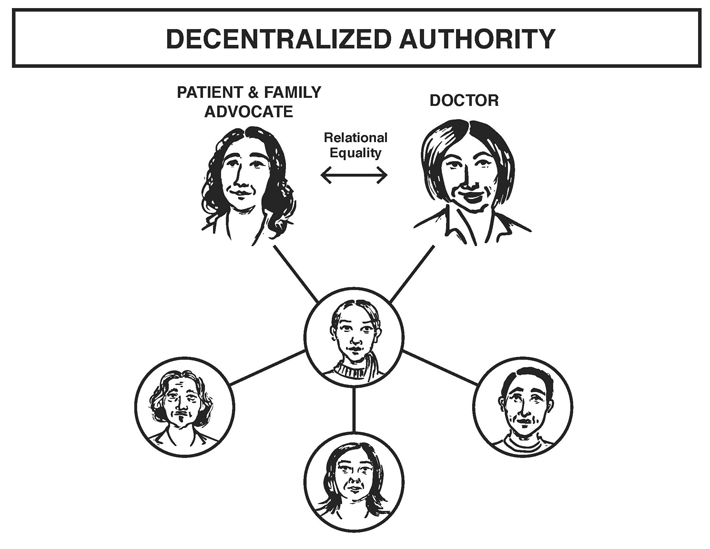

Our intervention relies heavily on decentralizing authority through relational equality, peeling off the layers of heroism that burden the doctor.

How do we do that? By weaving the PFA through the entire narrative, both from patient and hospital staff perspectives. The PFA is introduced to the staff form the very beginning through trainings and workshops. She meets with doctors and nurses before major meetings to hear the “cold hard truth”– they know her role is to make sure the difficult stuff gets dealt with.

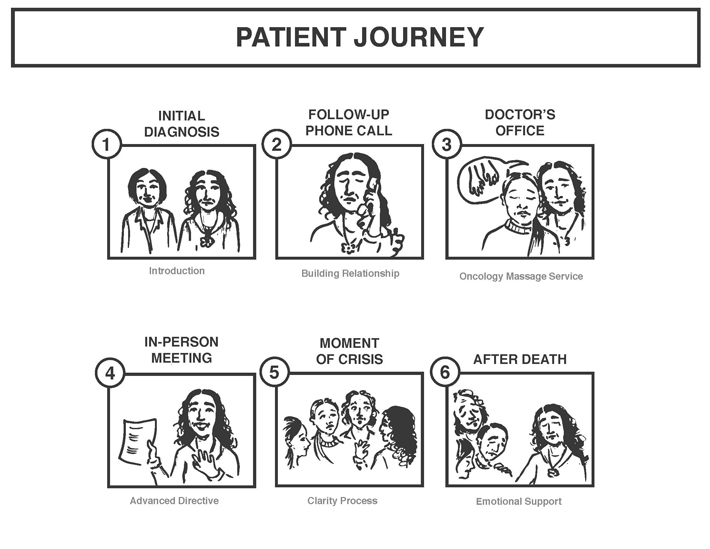

On the patient side, they meet their PFA from the initial diagnoses, and she guides them throughout their journey.

Even though the PFA may not have the same social status as a doctor, we believe that we can create relational equality through this trust building, and because she’s working with the doctor to serve families; they are introduced as a team.

A brief overview of important touch points of the altered patient experience looks like:

1) They meet Lisa at the initial diagnoses.

2) Lisa follows up with a phone call to build trust and relationship.

3) During a doctor’s appointment, Lisa sees how tense and stressed Sara is, and connects her to the hospital’s Oncology Massage Service.

4) As the cancer progresses, Lisa sees the family denying potential death. She recommends and guides through an Advanced Directive/ Living Will.

5) At the Moment of Crisis Lisa intervenes with the Clarity Process.

6) After Death, Lisa supports the family with phone calls, in person meetings, and additional referrals.

Save

Zooming out to the support structures for this role we envision, we have a health care system that gives equal weight to rescue and care culture. Where they are equally accessible and valued, allowing the overall system to adequately respond to changing patient needs.

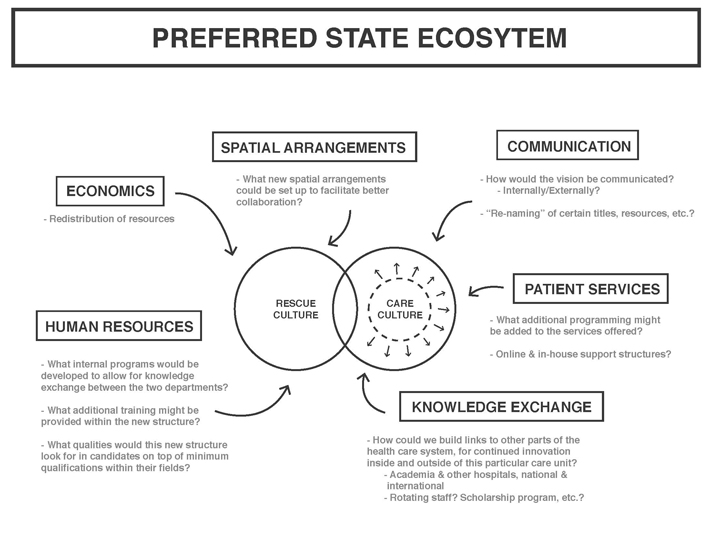

Creating a new organizational system would require consideration of a number of elements other than the ones we’ve already touched upon, like staff training and exchange. In our ideal state – situated within the realm of speculative design – we imagine an eco system of care, where the equal weight and increased collaboration is translated across human resources, economics, communication, patient services and knowledge exchange.

Speculative design may seem unrealistic in the much common search for quick and easy to implement solutions, but a lot of time knowing where we want to go – what purpose whatever new system you´re striving towards is serving – is in itself half the work. If we understand what we’re aiming for, we can take incremental steps towards that, based on the particular constraints and opportunities of the context where speculative design meets reality. This way design can also function not as a pre-packaged solution, but as a provocation and a conversation starter, opening up for a multitude of stakeholders to shape future design interventions in response to their particular context and goals.

Save